The maturing iPad and iOS system offer a a number of approaches and apps for use in jury selection, or voir dire. Here’s a review of a relatively new player JuryPad, recent updates to JuryStar and reference to old standbys using a spreadsheet or Bento. One caveat to all of these methods for jury selection: During attorney conducted voir dire, you need someone running the iPad. Attempting to track juror responses and engage in a meaningful give and take with jurors during questioning while simultaneously operating an iPad is just too complicated. [March 15, 2013: Original post omitted coverage of iJuror, now covered below].

JuryPad: iPad App for Jury Selection – Review

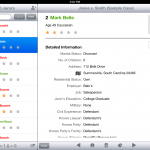

JuryPad ($24.99) offers a fairly intuitive and standard iOS interface. Large icons and text make it easy to navigate. JuryPad uses a form input method for gathering juror information during selection process or pre-populating with information prior to selection if you are in a forum that allows access to jury pool names in advance.

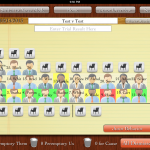

JuryPad lets the user set the rows columns for the pool which is very nice because not all courtrooms have the same number of chairs/rows for holding the pool. The user can then place the jurors in the appropriate pool seat as they reflecting the actual courtroom layout visually. Each juror is represented by an avatar reflecting the sex and race of the individual juror. The inclusion of race in each avatar is a nice feature for Batson issues and giving a quick visual as to what is going on.

From the courtroom/pool screen, juror detail information can be quickly accessed, and you can complete any unanswered questions and fill in new information as it arises. From the layout screen it is also very easy to strike jurors for cause, as a peremptory by either side or chosen for being a member of the jury. JuryPad accommodates both the ‘seat and strike’ method as well as the method where all questioning is conducted prior to exercising strikes at a bench conference. When seating jurors, once the designated number of necessary jurors has been met, the app pops up a box telling the juror that the selection process is complete.

Visual cues are also included for jurors who have been stricken, but it would be better if the app indicated whether the strike was for cause or which side exercised the strike. Additionally, the ‘custom’ jury selection questions only allow for ‘yes-no’ type questions. This is probably the greatest problem for use in jury selection as open ended questions are the preferred method of eliciting information and opinions from jurors. Additionally, ‘custom’ jury selection question templates are an all or nothing approach. You must select a single set of custom questions to include in each trial. This is unfortunate because there are discreet issues in every trial which lend themselves to template based questioning, but which do not arise in all trials. For example, in a civil tort case, liability might be conceded but there is still a need to question regarding bias in deciding damages. It would be better if individual modules of custom jury selection questions could be added, rather than being forced to pick one long outline.

Last, JuryPad offers the ability to share a single trial with other trial team members. Allowing one team member to create the basic jury selection plan and share it with all others is a smart move and an easy way keep everyone on the same page.

JuryStar: iPad App for Jury Selection

JuryStar ($39.99) has been around longer than JuryPad. The app was originally considered for review on release in December of 2011. Unfortunately, JuryStar used a ‘locked’ jury grid which made the app useless for anything other than the seat and strike method, and even that was questionable considering that jury rows and number of chairs vary from courtroom to courtroom. Several updates from the developer have cured this original limitation, allowing customization of the number of rows and columns for juror pool seating.

Unlike JuryPad, the app does offer a more flexible load of ‘custom’ voir dire questions. And, individual modules of questions can be loaded in as necessary. JuryStar also uses a ‘slider’ to rate jurors on each area of questioning. The slider compliments and makes possible open ended questions resulting in a more natural  information flow during of voir dire. As information is gathered and jurors rated, the rating summary at the bottom of the jury box changes to reflect the bias of the potential juror. For example, the rating for each area of questioning is displayed in the juror’s box, i.e. an abbreviation for SPD reflecting attitudes about special damages displays a number -5 through +5 and provides a total of all question areas at the bottom. The app also provides a ‘thumbs up’ or ‘thumbs down’ button which changes the color of the box from yellow to red or green. JuryStar gives the lawyer an easy reference to raise strikes for cause and intelligently exercise peremptories.

When exercising strikes, the juror is removed from the pool and placed in a box reflecting peremptory us, them or court stricken. The undo button, however, can be a bit finicky. During use, the undo button only works for the last juror stricken and stops working altogether if you go back to the voir dire screen. A small mistake here could lock you into a pool that does not accurately reflect the strikes and completely derail the setup in JuryStar.

JuryStar gets a bit hung up on the user interface end. The app is a little bit unintuitive and is not iOS standard. Accordingly, there is a bit more of a learning curve with JuryStar. Additionally, JuryStar operates only in portrait mode with no rotation to take advantage of the wider screen in landscape.

Overall, it’s a tough call as to which app is better. JuryPad wins not only on price, but also ease of use. JuryStar wins on feedback, ability to rate jurors during voir dire, and custom question templates but loses ground for it’s interface and undo function. Both would be recommended in the absence of any other approach and both certainly excel over the old scribbled notes on yellow legal pad method.

iJuror: iPad App for Jury Selection

Almost immediately after posting, the developer of iJuror contacted me asking to include that app in this post as well. iJuror ($19.99) provides many of the same features discussed above. But, iJuror offers just about the best over-all summary/visual feedback for rating each juror. Both color and rating can be made to appear, as well as race/sex on each individual juror. The panel can be customized and, best of all, roulette style pickers can be customized as well for quick data entry during selection on important key issues. While offering some benefits over JuryStar and JuryPad, iJuror is somewhat confusing in layout and user-interface. There are two modes for jurors, info and note, yet the notes field is contained in the info mode while none of the detailed demographic and stock info is detailed in the note mode. Additionally, answer space for custom text questions is limited to only about a single sentence. Exercising strikes is relatively easy, and jurors can be placed in the box by drag and drop. The app also offers two additional ‘in-app’ purchases: Juror Scoring ($4.99) and Juror Behavior ($9.99) which expand the capability of the app beyond initial voir dire and selection.

- iJuror for Jury Selection

Old Standbys for iPad Jury Selection

There are also a few old standbys for jury selection. The spreadsheet method, which still gets used from time to time, can be easily modified to incorporate a wide variety of issues and circumstances. Numbers on the iPad is a simple, easy to use spreadsheet app and can easily adapt to creating a jury selection template. It’s not that great, but it’ll do in a pinch. There’s also this old but simple Bento approach to jury selection developed here on MacLitigator some years ago. The Bento template is still my preferred method to this day mainly because of the filters built in which allow marking jurors as those to be stricken (either peremptory or for-cause) and then viewed as a final panel. JuryPad and JuryStar, however, are both getting very close to replacing that old Bento approach.